You Won’t Believe These Hidden Corners of Medina

Medina isn’t just about the Prophet’s Mosque—there’s a whole other side most visitors never see. I wandered beyond the main paths and discovered quiet alleys, centuries-old courtyards, and local spots humming with tradition. These hidden theme areas offer a deeper, more personal connection to the city’s soul. If you're looking for authenticity beyond the pilgrimage trail, you gotta check this out. While millions come each year to honor the spiritual heart of the city, relatively few venture into the surrounding neighborhoods where daily life unfolds with grace and quiet dignity. This quieter Medina, preserved in its architecture, routines, and community bonds, reveals a rich cultural tapestry that complements the sacred journey. Exploring these overlooked spaces isn’t about replacing the central religious experience—it’s about enriching it with context, color, and human connection.

The Heartbeat Beyond the Haram

At the center of Medina lies Al-Masjid an-Nabawi, the Prophet’s Mosque, a site of profound reverence and constant pilgrimage. Its vast courtyards, gleaming minarets, and spiritual aura draw millions annually, and rightly so. Yet, for many visitors, the experience ends there—confined within the boundaries of religious devotion and structured tourism. What often goes unnoticed is that the true cultural pulse of Medina beats just beyond this sacred perimeter. The neighborhoods radiating outward from the Haram carry a living heritage shaped by generations of residents who uphold traditions quietly but firmly.

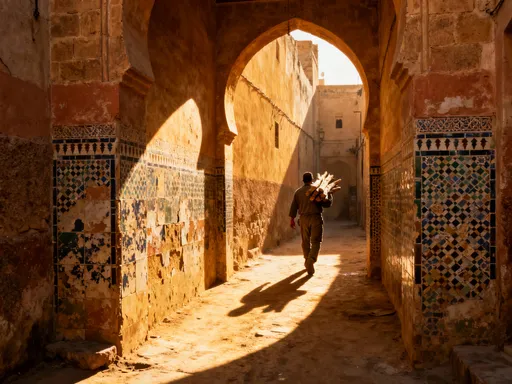

These areas are not marked on most tourist maps, nor do they appear in standard itineraries. They include old residential quarters like Al-Hujon, Al-Suwaiqat, and parts of Al-Madina Al-Qadeema, where the city’s historical identity remains embedded in the urban fabric. Unlike the bustling commercial zones near the mosque, these districts move at a gentler pace. Here, life unfolds in rhythm with prayer times, family gatherings, and seasonal customs. The streets are narrower, the buildings older, and the sense of community more tangible. This is where Medina’s cultural DNA is preserved—not in museums, but in everyday routines.

Exploring these lesser-known zones deepens one’s understanding of Medina as both a spiritual and social entity. It shifts the narrative from seeing the city merely as a destination of worship to recognizing it as a living, breathing community with its own rhythms and values. For travelers, this expansion of perspective fosters a more respectful and nuanced engagement. When you witness how families maintain ancestral homes, how elders gather in shaded courtyards, or how children play in alleyways lined with date palms, you begin to appreciate the continuity of life in a city that honors both its past and present. This balance between reverence and daily existence is what makes Medina unique among Islamic holy cities.

Al-Baqi’ and Its Quiet Neighbors

Just across the southern wall of Al-Masjid an-Nabawi lies Al-Baqi’ Cemetery, one of the oldest and most venerated burial grounds in Islam. While many pilgrims visit to offer prayers, few linger to explore the surrounding residential lanes that slope gently away from the mosque complex. These quiet streets, lined with modest homes and shaded walkways, form a transitional zone between the sacred and the everyday. Walking through them feels like stepping into a different dimension—one defined by stillness, reflection, and a deep sense of continuity.

The homes near Al-Baqi’ are often generations old, passed down through families who have lived in the area for decades, if not centuries. Many retain traditional architectural features such as thick mud-brick walls, arched doorways, and small courtyards designed to capture breezes during the hot summer months. The pace of life here is unhurried. You might see an elderly man watering potted plants at his doorstep, a woman hanging laundry in a shaded corner, or a group of children cycling down a narrow lane. These simple moments, unremarkable in isolation, collectively form the quiet heartbeat of Medina’s residential soul.

For visitors, walking through these neighborhoods offers a rare opportunity for contemplative travel. Unlike the crowded corridors of the mosque, these areas allow space for personal reflection. The proximity to Al-Baqi’ adds a layer of solemnity, reminding one of the transient nature of life and the enduring value of faith and community. At dawn or late afternoon, when the call to prayer echoes softly across the rooftops, the atmosphere becomes especially poignant. There is no rush, no pressure to perform—only the quiet dignity of a city that has witnessed centuries of devotion and daily life intertwined.

The Forgotten Courtyards of Old Medina

Scattered throughout the older districts of Medina are traditional Najdi-style houses, many of which remain inhabited despite the pressures of urban renewal. These homes are built around central courtyards—private, inward-facing spaces that serve as the heart of family life. The courtyard design, common in arid climates, provides natural ventilation and shade, making it an ideal retreat during the intense heat. Walls are constructed from compacted earth and stone, materials that absorb heat during the day and release it slowly at night, helping to regulate indoor temperatures.

Architectural details such as wooden *mashrabiyas*—latticed window screens—add both beauty and function. They allow airflow while preserving privacy, a crucial consideration in a culture that values modesty and family seclusion. Some homes still feature hand-carved doors and ceiling beams, evidence of craftsmanship that has been passed down through generations. Though modern renovations have introduced glass windows and air conditioning in some cases, many families strive to preserve the original design elements that connect them to their heritage.

Living in these homes is more than a matter of tradition—it’s a conscious choice to maintain a way of life rooted in simplicity and community. Residents often speak of the courtyard as a gathering place for meals, storytelling, and religious recitations, especially during Ramadan. It is where grandparents share stories with grandchildren, where neighbors drop by for tea without prior notice, and where the rhythm of life follows the sun and the prayer schedule. These homes are not museums; they are lived-in spaces where history and modernity coexist in quiet harmony.

For travelers, gaining respectful access to such homes—often through guided cultural tours or personal invitations—offers a rare glimpse into authentic Medina life. It’s a reminder that heritage is not just preserved in grand monuments but also in the everyday spaces where families continue age-old customs with quiet pride. The resilience of these architectural forms speaks to a deeper cultural endurance, one that values continuity, family, and environmental wisdom.

The Date Markets and Back-Alley Eateries

While the main souqs near the Prophet’s Mosque cater to pilgrims with packaged souvenirs and mass-produced goods, a different kind of market thrives in the backstreets near Suq Al-‘Aridh and surrounding residential zones. Here, the air is thick with the sweet scent of dates, roasted nuts, and freshly baked bread. These are the city’s true food hubs—places where locals shop, socialize, and preserve culinary traditions away from the tourist gaze. Stalls overflow with dozens of date varieties, from the soft, caramel-like *Rutab* to the rich, nutty *Ajwa*, long celebrated in Medina for their quality and spiritual significance.

Dates are more than just a food source in Medina—they are a symbol of hospitality, health, and tradition. It is common for families to offer dates and water to guests as a gesture of welcome, a practice rooted in Prophetic tradition. Many households maintain their own date presses, turning surplus harvests into date syrup (*dibs*) or dried cakes for winter storage. In these markets, vendors often come from farming families in nearby oases, bringing their harvest directly to the city. Conversations flow easily among regular customers, with recommendations shared about which dates are best for energy, digestion, or children’s snacks.

Nestled between these stalls are small eateries—unmarked, family-run kitchens that serve simple but deeply flavorful meals. You won’t find English menus or laminated price lists here. Instead, meals are served on low tables in shaded corners: slow-cooked lamb stews, fragrant rice dishes with saffron, and fresh flatbreads baked in clay ovens. Some spots specialize in *haneeth*, a traditional dish of tender meat slow-cooked in underground ovens, while others serve *jareesh*, a porridge-like dish made from crushed wheat and ghee. These meals are eaten communally, often with hands, reinforcing the social aspect of dining.

For visitors willing to step off the beaten path, these culinary experiences offer a direct line to Medina’s soul. They are not staged for tourists but exist as part of the city’s living culture. Approaching them with respect—dressing modestly, asking permission before photographing, and showing appreciation for the food and hosts—opens the door to genuine connection. In these moments, a simple meal becomes more than sustenance; it becomes a bridge between traveler and local, between curiosity and understanding.

Green Spaces and Urban Oases

In a city known for its spiritual significance, the presence of green spaces might seem secondary. Yet, Medina has long valued its natural retreats, particularly in areas like the Wadi al-Aqiq and pockets of palm groves scattered throughout residential zones. These green zones, though modest in size, play a vital role in urban life. They offer respite from the heat, space for family outings, and a connection to the agricultural roots of the region. Unlike formal parks with playgrounds and fountains, many of these areas are informal—patches of land shaded by date palms, with simple seating and running water for ablution or cooling.

Wadi al-Aqiq, historically a seasonal riverbed, remains a symbolic and practical green corridor. Though no longer a flowing stream, its wide, sandy expanse is lined with trees and used for walking, quiet reflection, and evening gatherings. Families often spread mats under the trees after Maghrib prayer, enjoying the cooler air and each other’s company. The area is especially popular during the summer months, when temperatures soar and the need for shade becomes essential. Local authorities have invested in maintaining these spaces, adding lighting, walkways, and waste bins to encourage responsible use.

There is also a growing awareness of the importance of preserving green areas amid rapid urban development. Community-led initiatives have emerged to plant native trees, protect existing groves, and promote sustainable landscaping. Some mosques and schools have incorporated small gardens into their premises, teaching younger generations about environmental stewardship through the lens of Islamic principles. The Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) emphasized kindness to all creation, including plants and animals, a teaching that continues to inspire conservation efforts today.

For travelers, visiting these green oases provides a different kind of spiritual experience—one rooted in peace, nature, and mindfulness. Sitting under a palm tree, listening to the rustle of leaves and the distant call to prayer, offers a moment of stillness often missing in busy pilgrimage itineraries. These spaces remind us that spirituality is not confined to mosques or rituals but can also be found in the quiet beauty of the natural world.

Cultural Hubs in Residential Districts

While Medina’s religious institutions are world-renowned, less visible are the informal cultural hubs tucked within its residential neighborhoods. These include family-run heritage cafes, community centers offering Quranic circles, and small workshops where traditional crafts like calligraphy and bookbinding are taught. Unlike formal museums or tourist centers, these spaces operate quietly, sustained by passion rather than profit. They are places where knowledge is shared intergenerationally, where young people learn Arabic script by hand, and where elders recite poetry from memory.

One such example is the growing number of heritage cafes—modest spaces that serve tea and snacks while displaying old photographs, traditional clothing, and handmade crafts. Some host weekly gatherings where guests listen to stories about Medina’s past, often told by long-time residents. These cafes are not commercial ventures but community projects aimed at preserving local memory. Similarly, informal calligraphy schools attract students who want to master the art of Islamic script, not for fame, but as an act of devotion and cultural preservation.

Quranic circles, or *halaqat*, are another cornerstone of community life. Held in homes, mosques, or community halls, these gatherings bring together men, women, and children to recite and study the Quran in a supportive environment. They foster a sense of belonging and spiritual growth, especially for families seeking deeper engagement beyond ritual prayer. Some circles focus on tajweed (proper recitation), while others emphasize understanding and reflection.

These cultural spaces reflect a Medina that is not frozen in time but actively nurturing its heritage. They show how tradition is not imposed but lived—passed down through daily practice, conversation, and shared meals. For travelers, participating in or observing these gatherings (with proper respect and invitation) offers insight into the city’s living soul. It reveals a community that values education, art, and faith not as separate domains but as interconnected threads of a rich cultural fabric.

Navigating Medina’s Hidden Layers: A Traveler’s Guide

Exploring Medina’s lesser-known areas requires more than curiosity—it demands respect, preparation, and cultural sensitivity. The best time to walk through residential neighborhoods is early morning or late afternoon, when temperatures are milder and families are more likely to be outdoors. Avoid visiting during midday heat or right before prayer times, when streets may be empty and homes closed.

Dress code is essential. Both men and women should wear modest clothing that covers shoulders and legs. Women are advised to wear loose-fitting garments and a headscarf, even if not required by law, as a sign of respect in religious and residential areas. Refrain from loud conversations, music, or photography without permission, especially near homes or private spaces. If you wish to take a photo, ask first with a smile and a simple gesture—most people will respond kindly if approached with humility.

Transportation options include walking, which allows for deeper immersion, or using local taxis and ride-hailing services for longer distances. Some cultural tours now offer guided walks through historic districts, led by residents who can provide context and facilitate introductions. These tours are invaluable for understanding the nuances of local life while avoiding unintentional disrespect.

When engaging with locals, a warm greeting in Arabic—such as *Assalamu Alaikum* (peace be upon you)—opens doors. Many people appreciate sincere interest in their lives, but avoid intrusive questions about family or personal matters. If invited into a home, accept with gratitude, remove your shoes, and offer a small gift if possible, such as dates or sweets. Always express appreciation for the hospitality.

Finally, remember that these spaces are not attractions but lived environments. The goal is not to document every corner for social media, but to experience Medina with humility and openness. By balancing reverence with curiosity, travelers can form meaningful connections and carry home not just memories, but a deeper understanding of a city that balances sacred duty with daily grace.

Uncovering Medina’s hidden theme areas isn’t about skipping the holy sites—it’s about deepening your journey. These quiet corners offer intimacy, authenticity, and a truer sense of place. For travelers seeking more than the expected path, Medina’s quieter rhythms might just be the most unforgettable part of the trip. In the end, it is not the grandeur of monuments but the warmth of human connection, the whisper of history in ancient walls, and the simple act of sharing a cup of tea in a shaded courtyard that leaves the lasting impression. Medina, in its fullness, is not just a destination of prayer—but a living story, gently unfolding.