Lost in the Lanes of Fes: Where Every Wall Whispers History

Walking through Fes feels like stepping into a living maze of stories. The air hums with craftsmanship, and every alley reveals centuries-old architecture that defies time. I didn’t expect to be so moved by stone arches, carved wood, and secrets tucked behind unmarked doors. This isn’t just a city—it’s a breathing masterpiece. If you’ve ever wondered what authenticity looks like, Fes will show you. Let’s explore the soul of Morocco, one hand-cut tile at a time.

Entering the Medina: First Impressions of a Timeless City

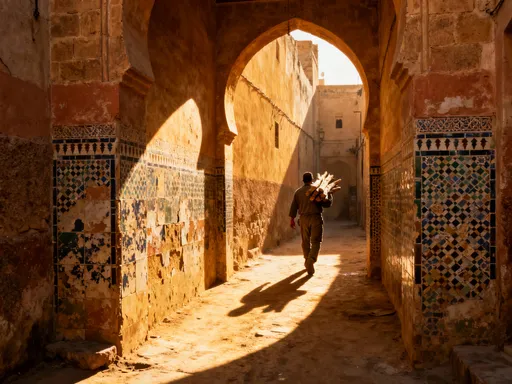

Stepping into Fes el-Bali, the ancient medina and heart of the city, is like crossing a threshold not only in space but in time. As one of the world’s largest car-free urban zones and a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1981, this 1,200-year-old city unfolds in a labyrinth of narrow alleys, vaulted passageways, and unexpected courtyards. The moment you pass through Bab Bou Jeloud, the iconic blue-tiled gate that serves as the ceremonial entrance, the modern world fades. No cars rumble here—only the soft clip-clop of donkey hooves carrying bundles of spices, carpets, or construction materials echoes against stone walls.

The sensory experience is immediate and overwhelming. The scent of cumin and cedar mingles with the earthy aroma of damp stone and leather from nearby tanneries. Voices rise from hidden workshops—metalworkers hammering copper, women bargaining for fabric, children calling to each other across rooftops. The light shifts constantly, filtering through latticework or reflecting off mosaic fountains, casting ever-changing patterns on the ground. This is not a museum exhibit; it is a fully lived-in city where over 150,000 people reside within its ancient walls, maintaining rhythms that have changed little in generations.

At first, the disorientation can be disarming. Maps are nearly useless; GPS often fails. The medina was not built on a grid but grew organically, shaped by topography, family needs, and centuries of adaptation. Yet this very chaos holds a kind of order—a logic born of community, climate, and culture. Over time, visitors begin to appreciate how the narrow streets provide shade in the summer and shelter from winter winds, how the elevation changes offer natural drainage, and how the clustering of homes around shared spaces fosters neighborly bonds. The city’s layout, once confusing, starts to feel intentional, even protective.

What stands out most is the harmony between the old and the present. While satellite dishes peek above ancient rooftops and electrical wires crisscross alleyways, they do not overpower the essence of the place. Residents move with purpose, balancing tradition and modernity with quiet dignity. Women in modern dress pass elders in djellabas; smartphones appear beside handwoven baskets. This coexistence is not forced but natural, a testament to Fes’s enduring ability to evolve without erasing its soul. To walk here is to understand that history is not behind glass—it is underfoot, in the air, and all around.

The Art of Moroccan Design: Understanding Zellige, Tadelakt, and Wood Carving

Fes is a masterclass in architectural artistry, where every surface tells a story. The city’s buildings are adorned with three signature elements: zellige tilework, tadelakt plaster, and hand-carved cedar wood. These are not mere decorations—they are expressions of identity, faith, and craftsmanship passed down through generations. Each technique reflects a deep understanding of geometry, material, and meaning, creating spaces that are both beautiful and spiritually resonant.

Zellige, the intricate mosaic tilework that covers walls, fountains, and floors, is perhaps the most iconic feature. Made from hand-chiseled terracotta tiles glazed in vibrant blues, greens, yellows, and whites, zellige patterns are painstakingly assembled without the use of grout. The designs follow complex geometric principles rooted in Islamic tradition, where infinite repetition symbolizes the boundlessness of the divine. Stars, polygons, and interlocking shapes form hypnotic patterns that seem to shift as you move. In Fes, artisans still cut each piece by hand using a metal hammer and anvil, a skill learned over decades. A single square meter of zellige can contain hundreds of individually shaped tiles, each placed with precision. Seeing a craftsman at work—his hands moving with practiced ease—reveals the patience and devotion embedded in every surface.

Equally remarkable is tadelakt, a waterproof lime plaster used in bathrooms, fountains, and sinks. Smooth to the touch and often finished in deep reds or earthy tones, tadelakt is polished with river stones to create a seamless, almost liquid surface. Unlike modern tiles, it has no grout lines, making it both hygienic and visually calming. The technique dates back centuries and remains a staple in traditional riads and hammams. What makes tadelakt special is not just its durability but its warmth—it feels alive, responding subtly to light and temperature. When applied to a fountain in a quiet courtyard, it enhances the sense of serenity, its gentle curve mirroring the flow of water.

Then there is the wood—especially cedar, prized for its fragrance, resistance to insects, and rich grain. In Fes, cedar is carved into elaborate geometric screens, door panels, and ceiling beams. The craftsmanship is extraordinary: motifs of stars, flowers, and calligraphy are chiseled in low or high relief, often with such fine detail that they seem more like lace than wood. These carvings serve both aesthetic and functional purposes—lattice screens, or moucharabieh, allow air and light to pass while preserving privacy. In homes and madrasas alike, the ceilings rise into intricate muqarnas, honeycomb-like vaults that diffuse light and create a sense of upward movement, as if drawing the eye—and the spirit—toward the heavens. Together, zellige, tadelakt, and wood carving form a visual language that speaks of balance, harmony, and reverence for the unseen.

Hidden Courtyards: The Secret Heart of Fassi Homes

Beyond the bustling alleys of Fes lie hidden sanctuaries—interior courtyards that serve as the soul of traditional Fassi homes. Known as riads, these residences are built around a central open space, often graced with a fountain, citrus trees, or a small garden. From the outside, they appear unassuming, their plain exteriors giving no hint of the beauty within. But step through the heavy wooden door, and the world transforms. The noise of the city softens; the air cools; light filters down from above, casting gentle patterns on tiled floors. This is architecture designed for reflection, privacy, and connection with nature.

The courtyard is more than a design feature—it is a philosophy. In a dense urban environment where space is limited, the inward focus creates a sense of expansion rather than confinement. The fountain at the center is both practical and symbolic: it provides cooling mist in the summer and represents purity and life in Islamic tradition. Water is channeled through small channels to each side of the courtyard, echoing the four rivers of paradise described in the Quran. Around it, rooms open onto arched galleries, their doors and windows framed with zellige and carved wood. The symmetry is deliberate, reflecting a worldview that values balance and order.

Many of these riads have been carefully restored and converted into guesthouses, allowing visitors to experience this way of life firsthand. Staying in a riad is not like staying in a hotel—it is like being welcomed into a home that has stood for centuries. Breakfast is served on a rooftop terrace with views of the city’s skyline, where minarets rise above a sea of red-tiled roofs. In the evening, the scent of orange blossoms drifts on the breeze, and the call to prayer echoes from nearby mosques. Time slows. Conversations deepen. The rhythm of the city, once overwhelming, becomes a gentle pulse.

What makes these spaces so powerful is their ability to foster stillness. In a world of constant noise and distraction, the riad offers a rare gift: quiet. The sound of dripping water, the rustle of leaves, the soft footsteps on tile—these become the soundtrack. Natural light plays across walls throughout the day, shifting from golden morning hues to deep blue shadows at dusk. There are no televisions blaring or phones buzzing; instead, there is reading, tea, and conversation. The architecture itself encourages presence, inviting you to sit, breathe, and simply be. In Fes, where history presses close, the courtyard becomes a space not of escape, but of return—to oneself, to beauty, to what matters.

Madrasas as Masterpieces: Learning and Beauty in Harmony

Among the most breathtaking examples of Islamic architecture in Fes are its madrasas—medieval Islamic schools that combined education with artistic excellence. The Bou Inania and Al-Attarine madrasas stand as testaments to a time when knowledge and beauty were not separate pursuits but intertwined disciplines. Built in the 14th century during the Marinid dynasty, these institutions were not only centers of religious learning but also expressions of civic pride and spiritual devotion. Today, they remain active places of worship and some of the best-preserved examples of Moroccan architectural artistry.

The Bou Inania Madrasa, located near the heart of the medina, welcomes visitors with a grand entrance leading into a serene courtyard. At its center, a rectangular fountain of white marble is flanked by students’ dormitories on two levels. The space is flooded with light, filtered through wooden latticework and reflected off zellige walls. Every surface is adorned: the lower walls with blue-and-white tilework, the upper sections with carved stucco featuring floral and geometric patterns, and the ceiling with intricate cedar wood. Calligraphy in Kufic script runs along the walls, quoting verses from the Quran that emphasize the value of knowledge, patience, and humility. Even the floor is a work of art—polished stone arranged in geometric precision.

What makes the Bou Inania exceptional is its continued use. Unlike many historical sites that exist solely for tourism, this madrasa still functions as a mosque. The prayer hall, with its rows of arched niches and mihrab pointing toward Mecca, is open for daily prayers. Visitors are asked to be respectful, removing their shoes and speaking softly. This living quality adds depth to the experience—you are not just observing history, but witnessing its continuity. The same stones that once echoed with the voices of students reciting theology now carry the murmurs of worshipers in quiet devotion.

Similarly, the Al-Attarine Madrasa, named after the nearby spice market (attarine means “perfumers”), is a smaller but equally exquisite structure. Its courtyard is more intimate, surrounded by student cells just large enough for a bed and a shelf. Yet the decoration is no less elaborate. The muqarnas dome above the entrance hall is a marvel of three-dimensional geometry, its honeycomb cells creating a sense of infinite depth. Light filters through stained glass, casting colored patterns on the floor. The craftsmanship here was meant to inspire awe and reverence—reminders that the pursuit of knowledge is a sacred act. These madrasas were not built for grandeur alone; they were designed to elevate the mind and spirit, using beauty as a pathway to understanding.

Craft Districts: Where Architecture Meets Industry

The souks of Fes are not just markets—they are living workshops where architecture and industry coexist in perfect harmony. Organized by trade, the souks form specialized districts: the metalworkers’ quarter, the weavers’ alley, the coppersmiths’ lane, and the famous tanneries. Each space has evolved to meet the functional needs of its craft, resulting in structures that are both practical and visually striking. Here, form follows function, yet never at the expense of beauty.

The tanneries, particularly Chouara Tannery, are among the most iconic. From a distance, the sight is surreal: a series of tiered stone vats arranged in a sunken courtyard, filled with vividly colored liquids—indigo, saffron, mint green, and deep red. Men in bare feet move between the vats, stirring hides with long sticks, their movements rhythmic and precise. The process, unchanged for centuries, uses natural dyes and pigeon droppings to soften the leather. Visitors view the scene from rooftop terraces, where shops offer mint tea and leather samples. The architecture here is utilitarian—thick stone walls, open-air platforms, ventilation shafts—but the result is unexpectedly picturesque, a blend of industry and tradition.

Equally fascinating are the metal and woodworking shops. In the copper district, artisans hammer sheets into lanterns, teapots, and trays, their workshops lit by natural light pouring through high windows. The layout allows for airflow and visibility, while the stone floors absorb heat and noise. Many of these shops are centuries old, their facades marked by hand-carved signs and intricate iron grilles. Inside, tools hang in neat rows, and half-finished pieces sit on workbenches. The owners, often third- or fourth-generation craftsmen, welcome questions and demonstrations. They explain how the shape of a lantern affects its light pattern, or how the thickness of a teapot ensures even heat distribution.

What makes these districts special is their authenticity. This is not performance for tourists—it is real work, real livelihoods. Children run errands, apprentices learn by doing, and bartering happens in Arabic and Berber as much as in French or English. The architecture supports this ecosystem: narrow entrances deter theft, shared courtyards allow for collaboration, and rooftop terraces provide rest spaces. Even the scent of the souks—spices, leather, wood shavings—becomes part of the experience. To walk through these districts is to witness a city that builds not just for beauty, but for purpose, where every structure serves both craft and community.

Preservation Challenges: Keeping Fes Alive Without Losing Its Soul

Preserving Fes el-Bali is not a simple task. While its historical significance is universally recognized, the pressures of modern life threaten its delicate balance. The medina faces challenges such as inadequate drainage, overcrowding, structural decay, and the impact of tourism. Many buildings, constructed centuries ago, lack modern plumbing or electrical systems. Some families live in homes without running water, relying on public fountains. As younger generations move to newer parts of the city, historic homes fall into disrepair, their ornate details crumbling under neglect.

Yet, efforts to protect the medina are ongoing. The Moroccan government, in partnership with UNESCO and international conservation groups, has launched restoration projects that prioritize traditional techniques over modern shortcuts. Instead of replacing zellige with ceramic tiles or using concrete to patch walls, artisans are trained to repair using original methods. Lime plaster is reapplied by hand, wood is carved to match historical patterns, and lost tilework is recreated based on archival photographs. These projects not only preserve architecture but also sustain livelihoods, employing local craftsmen and passing skills to apprentices.

One of the most successful initiatives has been the restoration of public fountains and mosques. These structures, once neglected, now serve as community anchors. Clean water flows again; prayers are held regularly; children play in the surrounding squares. In some cases, abandoned riads have been converted into cultural centers or guesthouses, generating income while maintaining historical integrity. Community involvement is key—residents are consulted, trained, and empowered to take ownership of preservation efforts. This bottom-up approach ensures that conservation does not become gentrification, displacing those who have lived here for generations.

Tourism, while a vital source of income, also poses risks. Overcrowding can strain infrastructure; poorly managed guesthouses may alter historic structures; and mass-produced souvenirs can undermine authentic craftsmanship. To address this, local guides are being trained to offer deeper, more respectful experiences. Visitors are encouraged to explore quietly, support artisan workshops directly, and stay in family-run riads. The goal is not to stop tourism, but to shape it—ensuring that it benefits the community without eroding the very qualities that make Fes special. Preservation, in this sense, is not about freezing the city in time, but helping it evolve with dignity.

Beyond the Tourist Path: Discovering Quiet Corners of Authentic Fes

While the main attractions of Fes are unforgettable, its true magic often lies in the quiet moments—the unscripted encounters, the hidden corners, the rhythms of daily life. Venture beyond the tanneries and madrasas, and you’ll find residential alleys where laundry hangs between buildings, elders sip tea on doorsteps, and children chase each other around fountains. These are not staged scenes; they are the ordinary, beautiful reality of life in the medina.

One morning, I followed a narrow lane uphill, drawn by the sound of water. There, tucked between two homes, was a small public fountain, its basin carved from stone, its spout shaped like a lion’s head. An elderly woman filled her jug, smiled, and offered a greeting. Nearby, a man swept the steps of a centuries-old mosque, its minaret barely visible above the rooftops. No signs marked the spot; no tour groups passed by. Yet the care taken with this space—the clean tiles, the fresh paint on the door—spoke of pride and continuity.

Another afternoon, I accepted an invitation to share tea with a carpet weaver. His workshop was small, lit by a single window, but filled with color—piles of wool in deep reds and indigos, half-finished rugs draped over looms. He spoke of his father and grandfather, both weavers, and how each pattern carried meaning: protection, fertility, blessing. We sat on cushions, sipped sweet mint tea, and listened to the rhythmic clack of the loom. There was no pressure to buy; only a desire to share. These moments—simple, human, unhurried—are what stay with you long after the trip ends.

Slowing down changes everything. You begin to notice details: the way sunlight hits a mosaic at 4 p.m., the call of a vendor selling fresh bread, the scent of jasmine in a hidden courtyard. You learn to navigate not by maps, but by memory and relationship. Shopkeepers remember your name; children wave as you pass. Fes reveals itself not in grand gestures, but in quiet accumulations—a smile, a shared silence, a cup of tea offered without expectation. In these moments, you understand that the city’s architecture is not just in its walls, but in its people, its traditions, its enduring spirit.

Fes isn’t just seen—it’s felt. Its architecture isn’t merely old; it’s alive, evolving, and deeply human. To walk its lanes is to witness resilience, creativity, and cultural pride etched in stone, tile, and wood. In a world chasing the new, Fes stands as a quiet rebel, reminding us that beauty grows from patience, skill, and soul. Visit not to check a box, but to remember what cities once were—and could still be.